At Cyber Agents, Inc., we often find ourselves tasked with determining a client’s location on a specific day and at a specific time. Fortunately, there are many ways a phone can record – and subsequently betray – location data.

In criminal trials, tower location data records (TLDR) can be obtained from cell service providers (CSP) to tie suspects to a crime. However, while TLDRs do show a relative area an individual may have been in, there are numerous other variables to consider: did the person of interest visit the area regularly? Was there an obstruction that could have caused the device to connect to another – more distant – cell tower? How long were they connected to the tower, and what is the range on the tower/cell phone? I have even had a case where the prosecution had attempted to use the TLDRs of a phone belonging to someone completely unrelated to the case. TLDRs provide useful data, but can leave a lot to be desired.

There are other ways of determining a client’s location; for instance, if they had a working cell phone with Google location data services turned on. It is possible to recover some location data on the phone directly, but the data may also be downloaded directly from a client’s Google account. The latter method often provides a more in-depth look at the client’s whereabouts for the day in question.

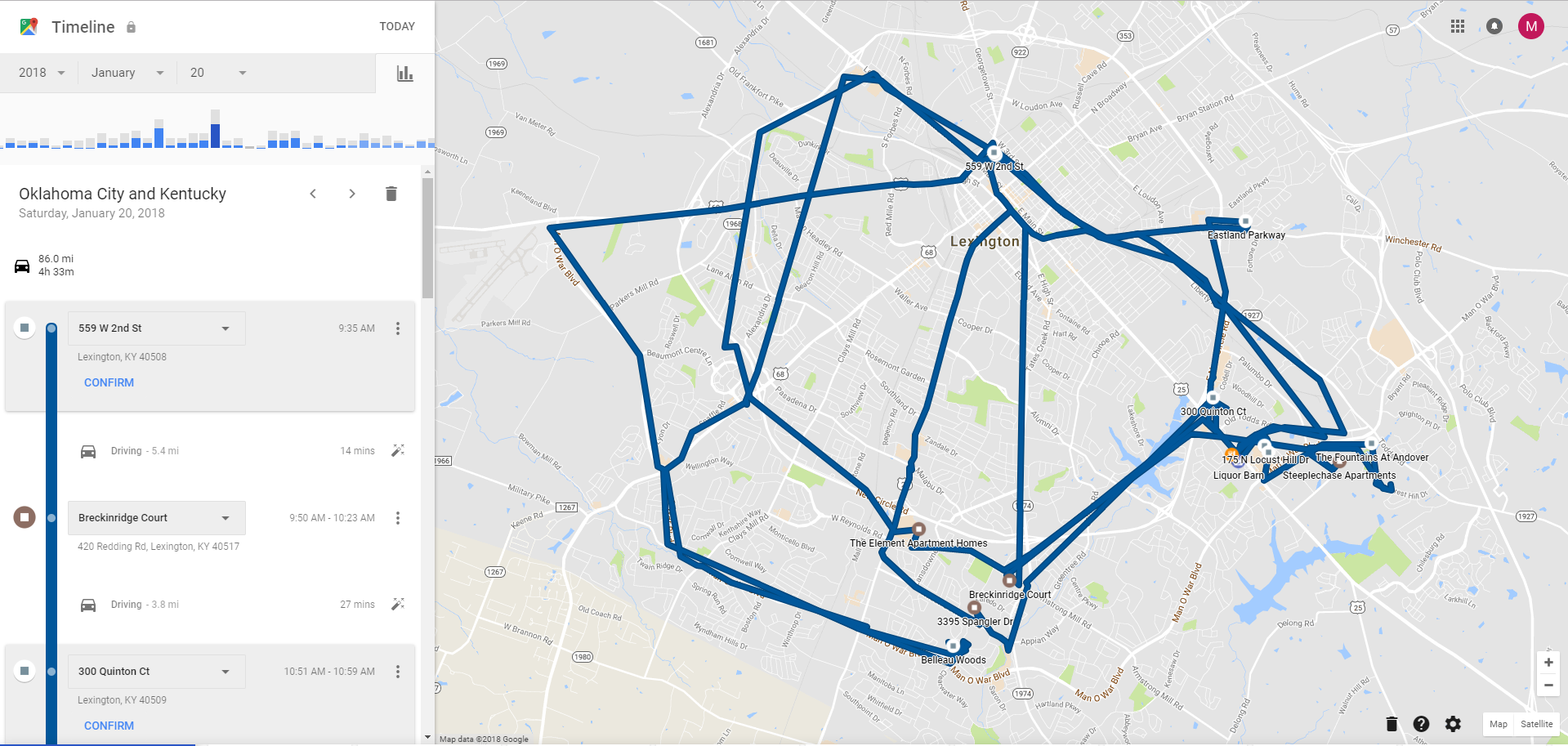

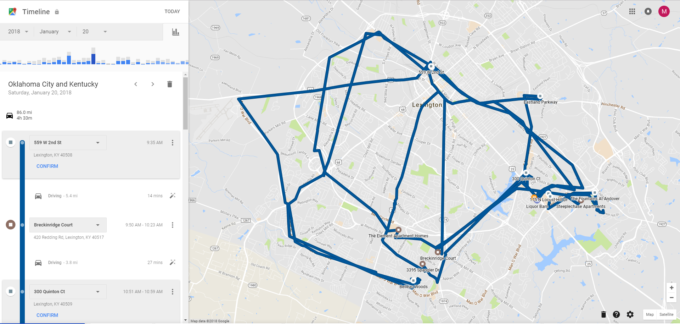

To demonstrate: I recently went apartment hunting. Throughout the day I had location services enabled on both my personal phone (OnePlus 5) and my work phone (LG G6). I traveled with my personal phone, and left my work phone at home. Afterward, I was able to access my Google Timeline and download a copy of my location data from that day. You can download it in KML format to use in Google Earth, or JSON format to use in Google Maps.

I’d also like to note that the times represented in the downloaded document are in UTC time. When viewed from your account page they should be your designated time zone. I manually converted the times during this narrative to reflect my current time zone (EST = UTC-5 and EDT = UTC-4).

A copy of an entire day’s location data will give you some overlap into the preceding day and the following day. The data we are looking begins at 3:35 PM on 19 Jan. 2018, and ends at 5:41 PM on 21 Jan. 2018. I remained at the same location from just before midnight on 20 Jan. 2018 until the first movement at 3:35 PM; Google exports the location recorded at midnight whether that entry begins hours or minutes before.

After importing the KML file into Google Earth, my entire day is mapped out with lines drawn between stopping points to indicate whether I was walking or driving. While the map does not show the precise route I took between points, it does show a direction of travel, arrival times, and departure times. During the driving portions multiple points are recorded and are logged as driving points. Location data was not available for my stationary device, the LG G6.

Still, this is not a perfect method. Some points are off by a significant distance, such as my apartment. But, Google location data does give a more precise area than TLDRs. Whenever possible, try to match any questionable locations with those found logged on the cell phone.

Notably, this timeline data can be altered by a user. The user can delete, modify, and view the data – which is logged in the account’s My Activity page. A user can also “snap” the plotted paths to the nearest roads which alters how the data is displayed in the map, but does not change times.

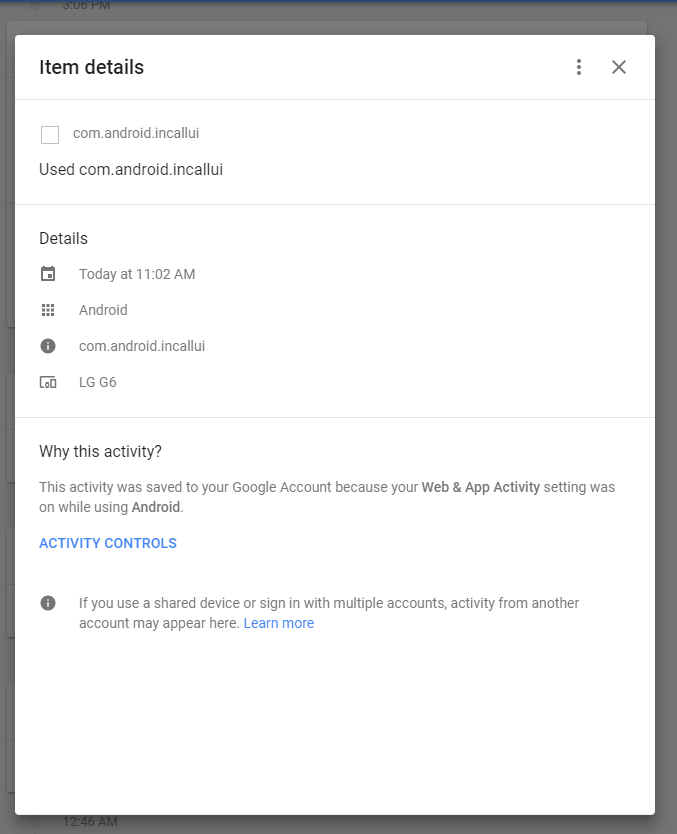

It is possible to have two devices logged in to the same Google account, and I have not been able to determine if/how Google separates the data from these devices. However, you can get an idea of what device was in use from the account history. It appears if an application is used that is manufacturer specific, you can determine which device was in use. For example, I was logged in to my account on my LG G6 as well, and found data showing access of an LG application. There was also some logged Android activity that showed up as coming from my G6.

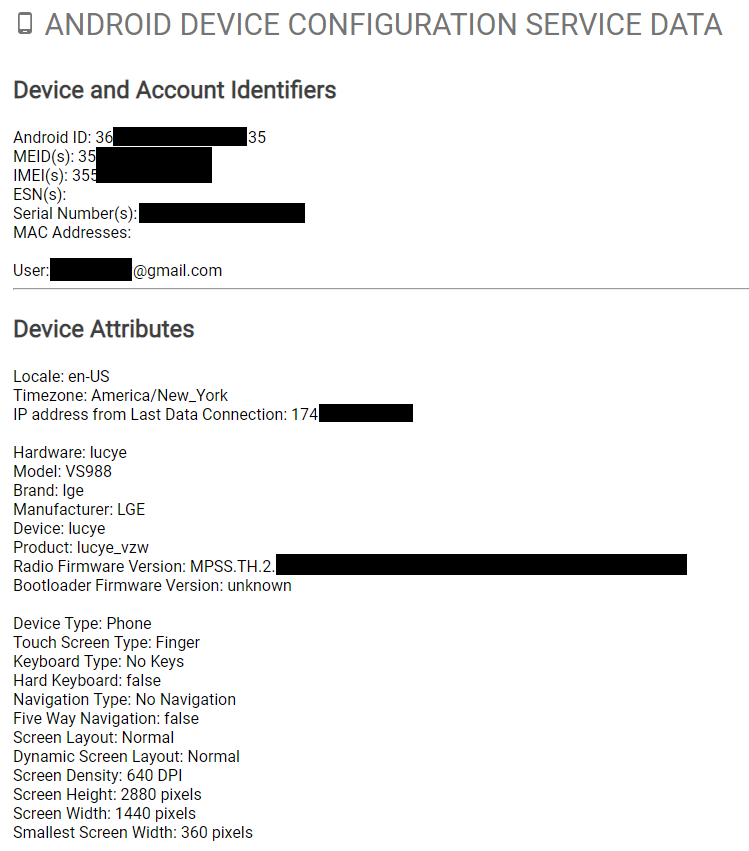

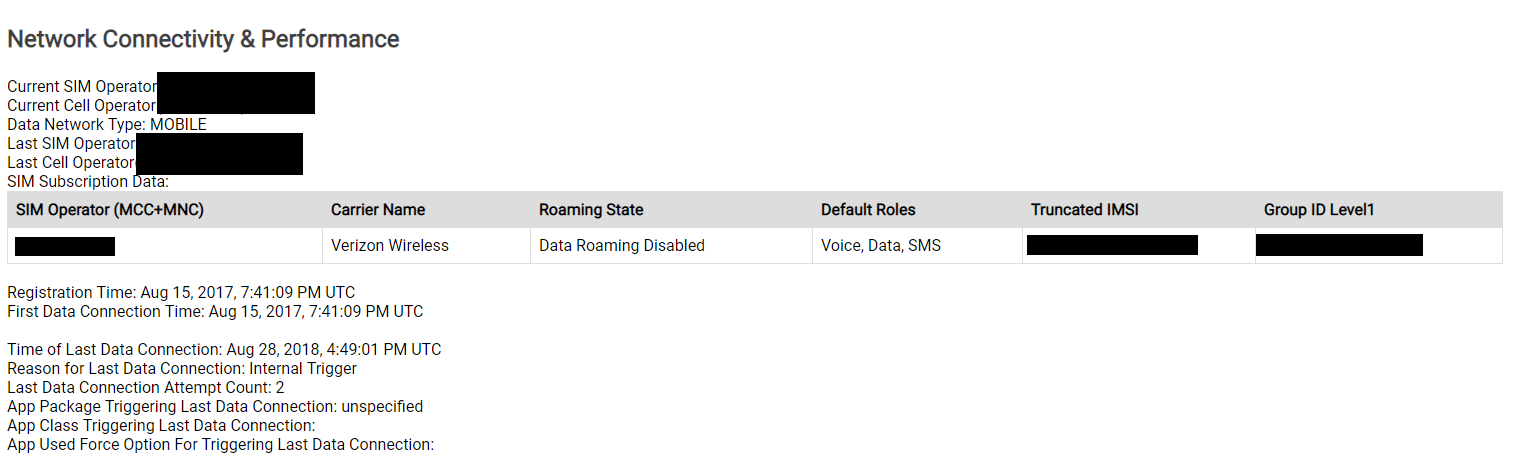

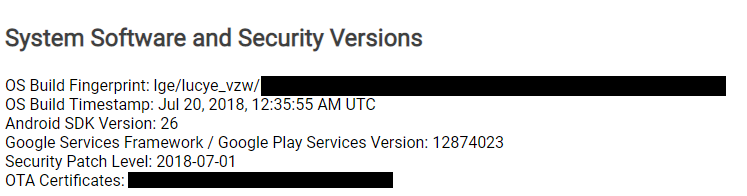

This is not entirely indicative of use of a specific phone, but since the logged-in device’s data isn’t provided in the “takeout”, it can indicate the use of another device. Google now allows the user to download the activated devices (phones/tablets) on the account. This can reveal vital information such as: when the device was activated on the account, make/model of the device, and the last known IP address on the CSP network. This data can be found under the “Android Device Configuration Service Data” (ADSCD) section of the takeout package. Below is some (partially redacted) info on my LG G6’s ADSCD.

I’ll note that the populated “Serial Number(s)” field was incorrect, but all the other data about the hardware and software were correct. If you think a suspect or client had been using a device that has not been preserved, this data may be enough to compel him/her to turn it over for review.

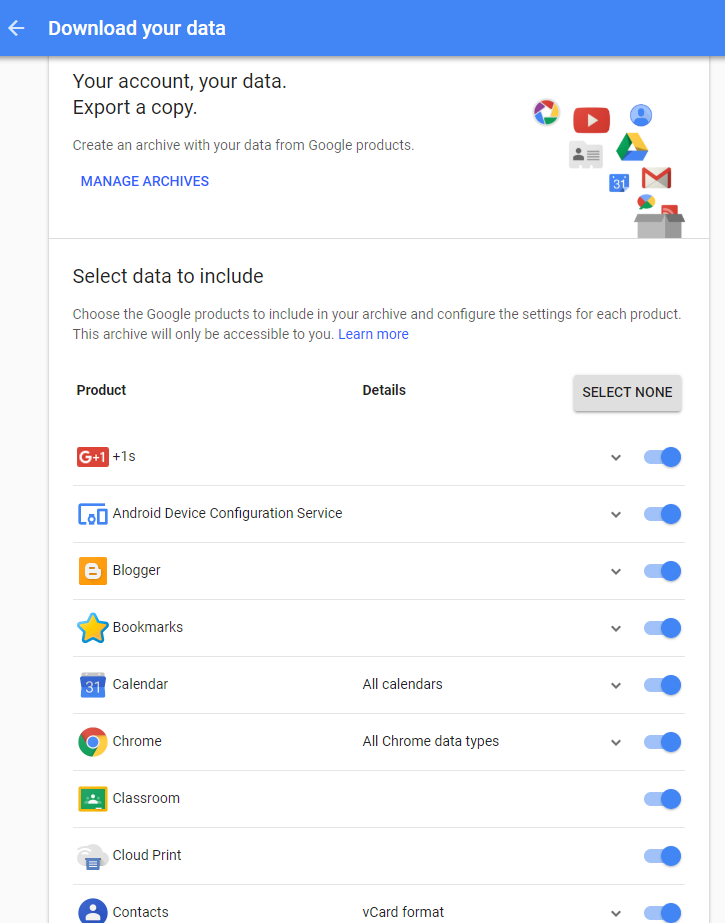

Other data accessible by obtaining a “takeout” of the Google account includes: Browsing/Search History, Calendar data, Emails, Maps searches, Play Store pages/downloads, and YouTube search/watch history. All these sources can be used to link activity on a phone if you have the corresponding data dump.

Gaining access to someone else’s Google account can be an ordeal. The client often does not want anyone accessing their personal information. The data it contains is fundamentally pertinent to most cases so preservation of the data should happen quickly. As with preservation of digital data on devices, so must we preserve account data. Google’s location data could put a person within 10 yards of a crime scene or 10 miles away.

Do you have a case that requires location reconnaissance? Contact us below.

4 thoughts on “Google Location Data (Part 1)”

Comments are closed.